I’ve always been a fan of ultraportable laptops, from the venerable ThinkPad 500 to the ever-so-slightly more modern ThinkPad T460s that I currently use. Back in 2013, I got my hands on a ThinkPad called the 240X, which was particularly confusing, as the X240 was just being released at that time!

Introduction

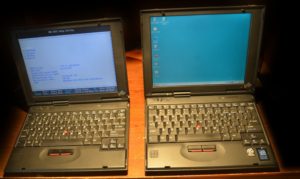

The ThinkPad 240 was a series of subnotebook that IBM released from roughly June 1999 to February 2001. It came in three variations: 240, 240X, and 240Z. The 240Z was only sold in Japan, but maxed out at a 1024×768 screen resolution, whereas the other models had 800×600. All screens were 10.4″ and active-matrix. The 240 has TWO battery options: a smaller (11.1V 1.4AH) pouch-style battery that sits flush with the bottom of the laptop, and a larger (11.1 3.1AH) 18650-populated battery that sticks out of the bottom of the laptop, doubling as an incline and letting you set the laptop on a desk at an angle.

Specifications

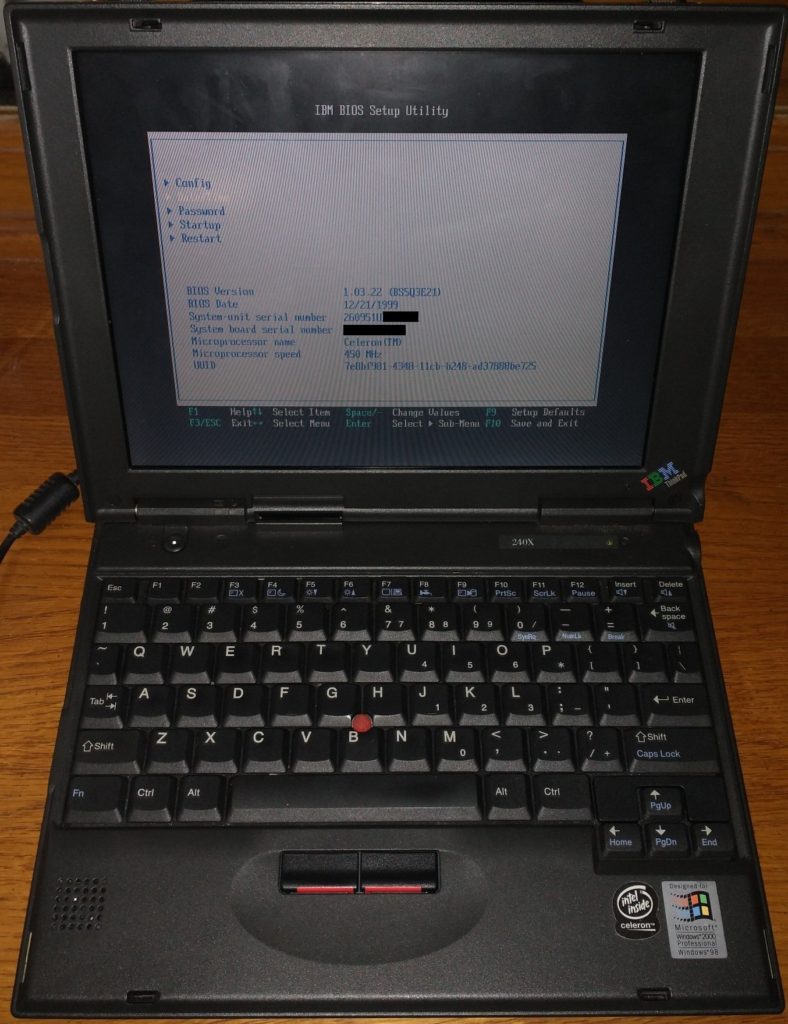

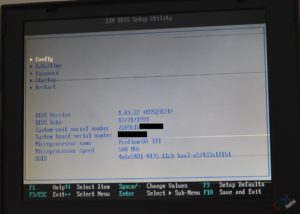

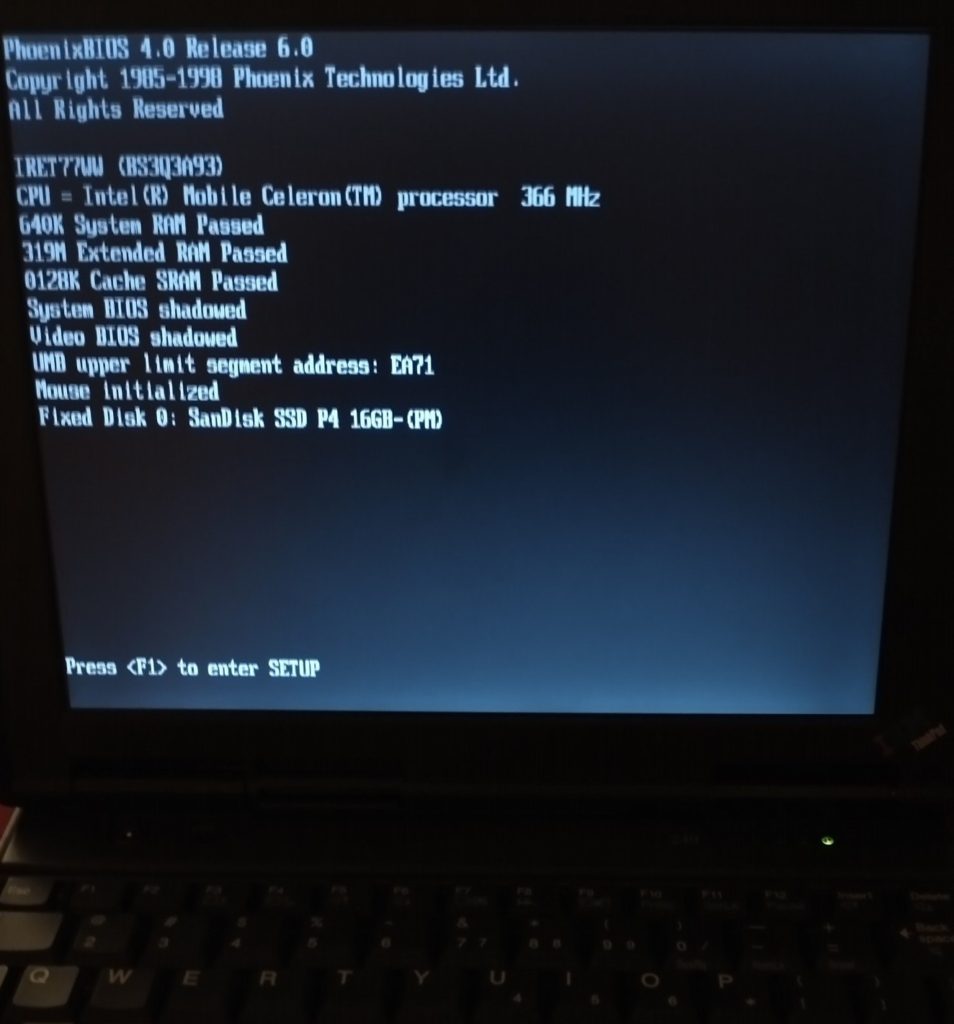

For processing power, the base 240 is stuck with an Intel Celeron running at 300, 366, or 400 MHz. The 240X starts with a 450 MHz Celeron, but some models had a Pentium III running at 500 MHz! I’ve never seen a 240Z in-person, but they offer either a Celeron at 500 MHz or a Pentium III at 600 MHz. Unfortunately, the CPU is soldered on, so there are no easy upgrades.

One oddity about the 240 series of ThinkPads is that, while the 240 allows for up to 320 MB of RAM, the 240X (which is otherwise the superior version) only allows for a max of 192 MB. This is due to the different Northbridge chipsets used: the 240 uses the Intel 440DX (82443DX) which allows for up to 512MB, whereas the 240X uses the Intel 440MX (82443MX) which is limited to 256 MB of RAM. Since both models of 240 have 64MB soldered in, and only one actual RAM socket free, both are essentially maxed out with a single 128MB SODIMM.

For an ultraportable, the 240 has plenty of ports: RS-232 Serial, Parallel, VGA, PS/2, a single CardBus PCMCIA slot, and a USB 1.0 connector. The Serial, Parallel, and VGA Ports have rubber covers, but they are not attached, so it’s incredibly rare to find a 240 in the wild that still has these covers.

It also has a connector for an external floppy drive, which is actually an UltraSlimBay floppy drive (like the one used in the ThinkPad 600) in a fairly large external enclosure. The enclosure has a latch, so you can swap out drives easily. Unfortunately, the 240 cannot directly boot from an external CD Drive, but if you have an external floppy drive set up, you can boot from a “PLOP” Floppy, and from there, boot off of a USB Flash Drive. I’ve done this successfully more than once, although it’s extremely cumbersome and often requires a few tries before it works. For internal storage, the 240 came with a standard 2.5″ EIDE spinning hard drive, between 6.0 and 12.0 GB in capacity.

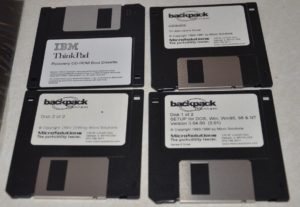

Some ThinkPad 240s came with an external CD-ROM Drive that plugs into the CompactFlash slot, however the only external CD Drive I got with any of mine was a Backpack (Parallel Port) CD-ROM Drive.

Issues

The 240 has a few weak points, of course. First, it’s unique for a ThinkPad in that it has a built-in rechargeable CMOS/RTC battery, much like the Toshiba laptops of the mid-1990s. These typically charge when the machine is running (not in standby or off), although I haven’t used a multimeter to confirm this like I have on the Toshibas. This is mainly because, unlike the Toshiba RTC batteries which are connected via a BERG Pigtail connector, or the ThinkPad 770 where it’s actually socketed, the one on the 240 is soldered! (Note that the ThinkPad 500 has the same arrangement.)

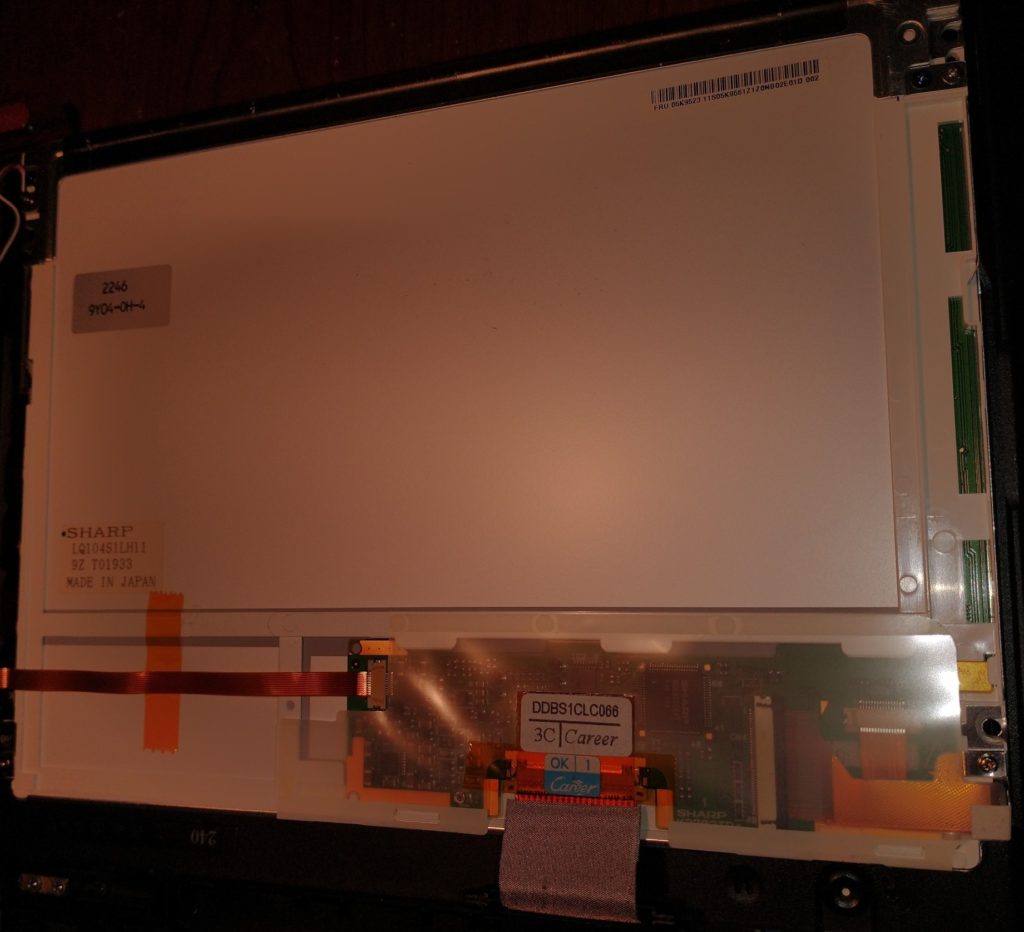

Second, the screen connector is notoriously fragile on both sides, and has worked its way loose on different sides of several of my 240s over the years. Usually this can be fixed by using DeOxit and reconnecting both sides of the screen cable, followed by reinforcing the copper tape on the motherboard side. However, I have read that many people had issues with cold solder joints, where the connectors themselves would separate from the motherboard. I did have one very bizarre issue where certain colors on the screen would randomly change, similar to a palette shift (also known as color cycling). This led to some unexpected results when I tilted the screen:

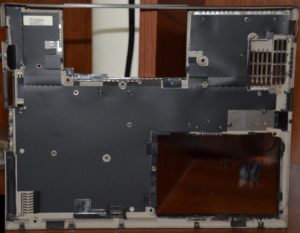

Third, the motherboards seem to completely fail on ThinkPad 240s more than any other model I’ve worked with. I’ve had to replace motherboards on at least 3 of my 240s over the years! One of them refused to even begin to power on, one would power on but not POST, and the third one gradually started having power issues until it stopped POSTing. Fortunately, a seller on eBay had a large inventory of new-in-box sealed 240 motherboards for $10 each, so for a long time, I got away with just buying one each time I needed to do a replacement. However, this is obviously not sustainable as these machines get older, so I kept the old motherboards in case somebody figures out the actual problem someday, as it’s certainly not visually diagnosable. 1999 was roughly the start of the capacitor plague (which ended around 2007), but it was before the massive switch to lead-free solder that caused longevity issues in literally 90% of my 2005-era ThinkPads, so it’s hard to tell what’s failing.

My Experience

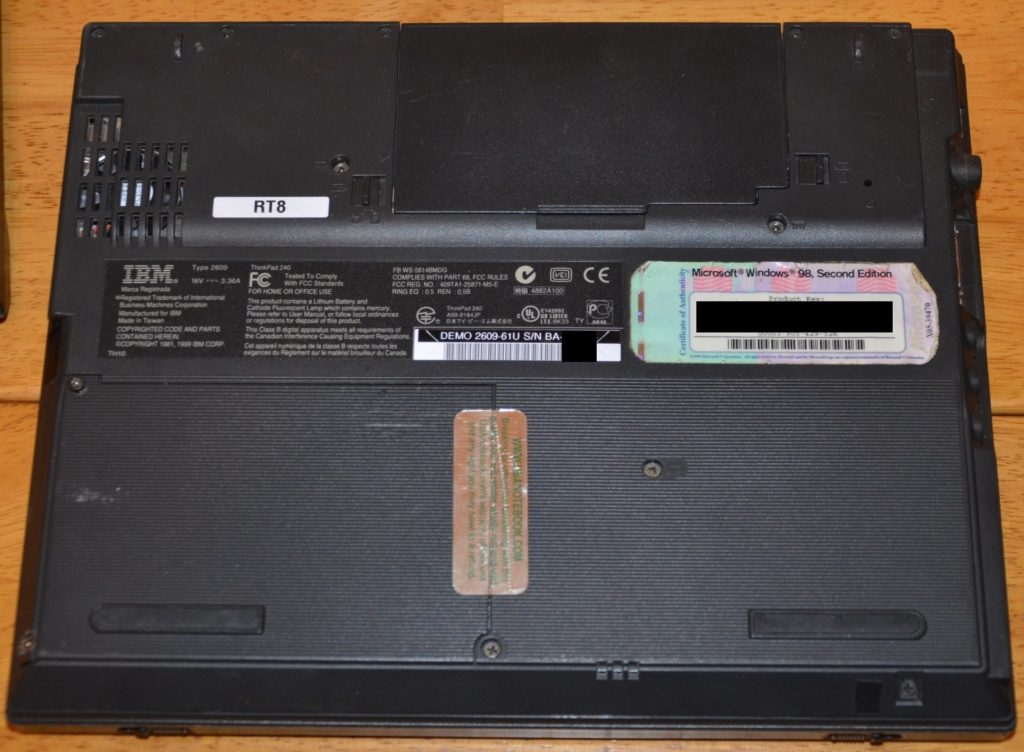

When I received my first 240X in 2013, I was pleasantly surprised by how lightweight it was: just over 3 lbs (1.5 kg). When I inspected it further, I noticed that the serial number sticker had the word “DEMO” written on it! While this could mean it was a prototype, it’s more likely that it was simply a demonstration machine, used internally at IBM to showcase the laptop’s features to vendors or other companies. If anyone knows, please leave a comment.

The original spinning IDE hard drive was quickly replaced with a dual-CompactFlash-to-IDE, which the BIOS actually correctly recognized as both a primary and secondary IDE Drive! Since CompactFlash-to-IDE adapters are generally passive (no active circuitry), the speed of this resulting “SSD” is effectively limited by the speed of the CompactFlash card (or how fast your ATA Bus is – the 240 shipped with ATA-66 drives).

Note that, starting in January 2016, I would convert all of my laptops to mSATA+IDE, but back in 2013, CompactFlash was still the way to go.

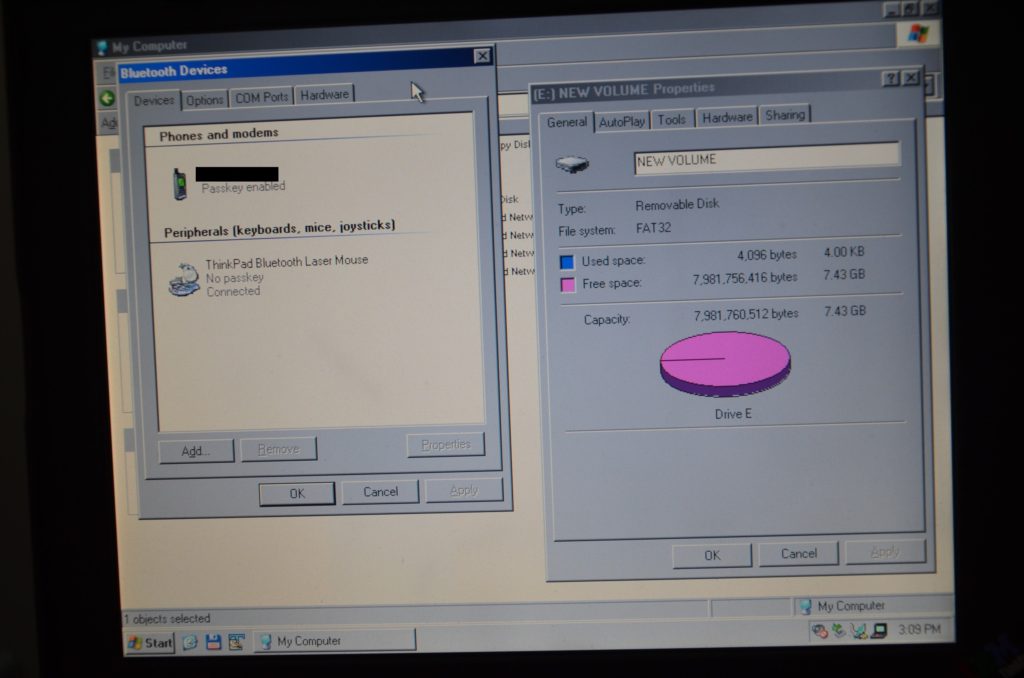

To max out my 240X, I bought a unique type of CardBus card that contained 1 USB 2.0 Port, but also had a RETRACTABLE antenna for built-in Bluetooth. By putting a nano USB Wireless-N “dongle” into this USB Port, I had what was effectively a removable Wi-Fi/Bluetooth Combo card (allowing me to use a Bluetooth mouse), while still having the built-in USB 1.0 Port on the right of the laptop for something else. Here’s a picture of the same card in my ThinkPad X24:

As I mentioned before, the 240X is limited to 191 MB of RAM. Fortunately, even with only 191 MB of RAM, Windows XP is efficient – and back in January 2014, I put this to the test. I loaded Adobe Photoshop, multiple LibreOffice documents, the Bluetooth stack, some musical composition programs, and a bunch of utilities open simultaneously. My total memory commit at this point ended up being 320/192 MB, but since I was able to fairly safely use one of the two CompactFlash cards as a pagefile, there was very little delay (maybe a half second) when switching programs. Obviously, using a CompactFlash card in this manner wears it out fairly quickly, even when using an industrial model, but I had to try it.

The onboard audio is another big difference between the 240 and 240X. The original 240 uses an ESS AudioDrive (ES1946) for audio, which sounds absolutely beautiful when listening to MIDI Files. The 240X, on the other hand, uses a Crystal CS4281. I’ve always been a huge fan of the ESS Solo found on my NEC Ready tower that I got in 2000 (which still works, AMD K6-2 and all), but I do enjoy the Crystal CS4326B in the Hitachi Flora 210 and the CS4237B in my ThinkPad 380Z (although that one often sounds incorrect, or choppy, when playing back certain MIDI patches).

Ultimately, the difference in audio chips can lead to fairly major differences in compatibility. For example, the ESS in the 240 is (by far) more compatible in pure MS-DOS than the 240X’s AC’97-based Crystal is. They also use different video cards, with the 240 using a very-common-for-the-time NeoMagic MagicGraph 128XD (2MB), and the 240X using a less-compatible Silicon Motion Lynx EM+ (2MB). A fairly comprehensive compatibility matrix can be found here, although its relevancy for “general use” scenarios has been disputed. Note that, like many laptops of the time, the scaler does not anti-alias the image when stretching it full-screen. However, it’s not the end of the world to run games unstretched, as the screen on 240 and 240X models is only 800×600 anyway, so the border around the image isn’t too large.

Although I rarely cover the specifics of ThinkPad keyboards on this website, it’s worth mentioning that the feel of the ThinkPad 240 is crisper than many of the others I’ve experienced. This is even true, albeit less so, for the heavily worn 240 keyboard that I have – it still feels incredibly responsive. The layout of the keys was reduced to, in IBM’s words, “95% size of current standard ThinkPad keyboards”, but the keys that were reduced in size are less commonly used. Despite the non-standard layout, the ThinkPad 240 (much like the IBM PC110) manages to technically squeeze seven rows of keys into the keyboard.

Conclusion

The ThinkPad 240 aged incredibly well in many ways, mostly because of its inclusion of a USB port and ability to add USB 2.0 ports. It was forward-thinking, using pouch cells instead of 18650s in the smaller battery pack, which reduced the overall thickness and weight of the laptop. Lastly, the fact that the top model uses a Pentium III is astounding, as it adds several extra years of software range that the 240 lineup can handle. The rechargeable CMOS/RTC battery can either be a help or a hindrance, depending on your point of view, and the reduced-size keyboard may affect some touch-typists (although I never had an issue with it feeling cramped). There’s also something charming about plugging a modern 128 GB Flash Drive into the USB Port to more-than-20x the capacity of storage that the machine shipped with in 1999.

NOTE: While I was in the middle of writing this article, the YouTube channel “This Does Not Compute” released a video on the ThinkPad 240. Since Colin was nice enough to link to this website for his Toshiba Libretto and ThinkPad 235 videos, I figured I should return the favor.

Revised on January 31, 2023

Do you have any links for recommendations on hard drive options?

I’ve just got one of these but unfortunately it’s missing its hard drive.

While the 240 uses a standard 2.5″ 44-pin IDE laptop hard drive, it unfortunately uses a proprietary caddy/connector. You can see a picture of this near the bottom of the article, where I show how I replaced the hard drive with an mSATA-to-IDE, but kept the caddy/connector so it would still physically fit and work.

I was working at IBM from ’93-’08. I really hated the Thinkpad 240 as all IBM departments had one as a beat up loaner laptop when your laptop died and still waiting for your shinny new latest Tseries.

Apparently the Thinkpad 240 was a very poor seller. I recall all jokes about the many skids of them that were sent to IBM sites as the loaner machines. IBM was terrible at provision sales on new machines but never wanted millions of dollars of orders pending.

“the motherboards seem to completely fail on ThinkPad 240s more than any other model I’ve worked with. I’ve had to replace motherboards on at least 3 of my 240s over the years!”

Mine just died as well, so frustrating. Surely it can’t be just you, but while there’s lot of info about the bad soldering affecting the T4x or blink of death on the T2x, there’s nowhere else talking about the 240 dying more often than they should afaik. Do you know of anyone else reporting such issue? Have you or anyone done some investigation on this?

I haven’t seen any discussion on this either. It seems like the 240 was too early to be affected by the switch to lead-free solder, and possibly a little too early to be affected by the capacitor plague.

Two of my 240s would fail by just powering on – no POST, nothing on screen. The other one worked, but seemed to have faulty power, as it would shut off randomly.

If I still had a faulty 240 that was fully assembled, I would plug in a “POST Card” to get a hint where the POST process is failing. These are devices that you plug into a PCI, ISA, Parallel, or USB Port (Parallel in the case of the 240). They have either a series of LEDs or a digital readout, and show each process of the POST as it happens. Watching where this stops, you can get a good idea of what’s failing (in the case of my ThinkPad 755CX, it was actually going into an infinite loop!)

I had no idea that you could get POST cards that plug into the parallel port on laptops! This is very helpful.

You absolutely can! The catch is that they need to be powered via USB (or some other 5 Volt source). I just use a portable USB power bank, and it works fine. They also require a BIOS that supports sending POST codes over the parallel port, but from what I’ve seen, anything IBM-based does this.